Fairy tales transport us to faraway lands that exist out of time. In much-loved and endlessly retold stories overflowing with kings and queens, castles and carriages, feasts and riches, we find adventure, community, happiness and love.

Celebrating classic tales of enchantment, transformation and caution, together with contemporary retellings by creative storytellers, the exhibition explores how these stories have held our collective fascination for centuries, and how, in the hands of artists, designers and filmmakers, they offer insights into our contemporary world.

Buy Tickets to ‘Fairy Tales’

Until 28 April 2024

Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane

‘Fairy Tales’ unfolds across three themed chapters. ‘Into the Woods’ explores the conventions and characters of traditional fairy tales alongside their contemporary retellings. ‘Through the Looking Glass’ presents newer tales of parallel worlds that are filled with unexpected ideas and paths. ‘Ever After’ brings together classic and current tales to celebrate aspirations, challenge convention and forge new directions.

Travel with us in our weekly series through each room and theme of the ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) as we place a spotlight on some of the works on display.

DELVE DEEPER: Journey through the ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition with our weekly series

EXHIBITION THEME: 8 Through the Looking Glass

Through the Looking Glass

‘Through the Looking Glass’ — the second major theme of the exhibition — brings together art, film and design that embrace exploratory stories of fantastical parallel worlds. Social change in the nineteenth century saw the emergence of children’s literature as a distinct genre. Industrialisation and print technologies, education reform and a growing leisured middle class contributed to the development of the concept of ‘childhood’ as an important stage in life. Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland 1865 and L Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz 1900 are examples of tales that changed society’s views of children by emphasising their enchanted perspective on life.

Drawing on the wonder of the childlike imagination, the ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition presents works that straddle the divide between everyday reality and extraordinary realms, where wonder, empathy, curiosity and compassion are often imperative for survival. These ideas play out in images of puppets, toys, snow globes and clocks; twirling mushrooms and flying houses; and immersive, otherworldly gardens full of unusual creatures and magical pathways.

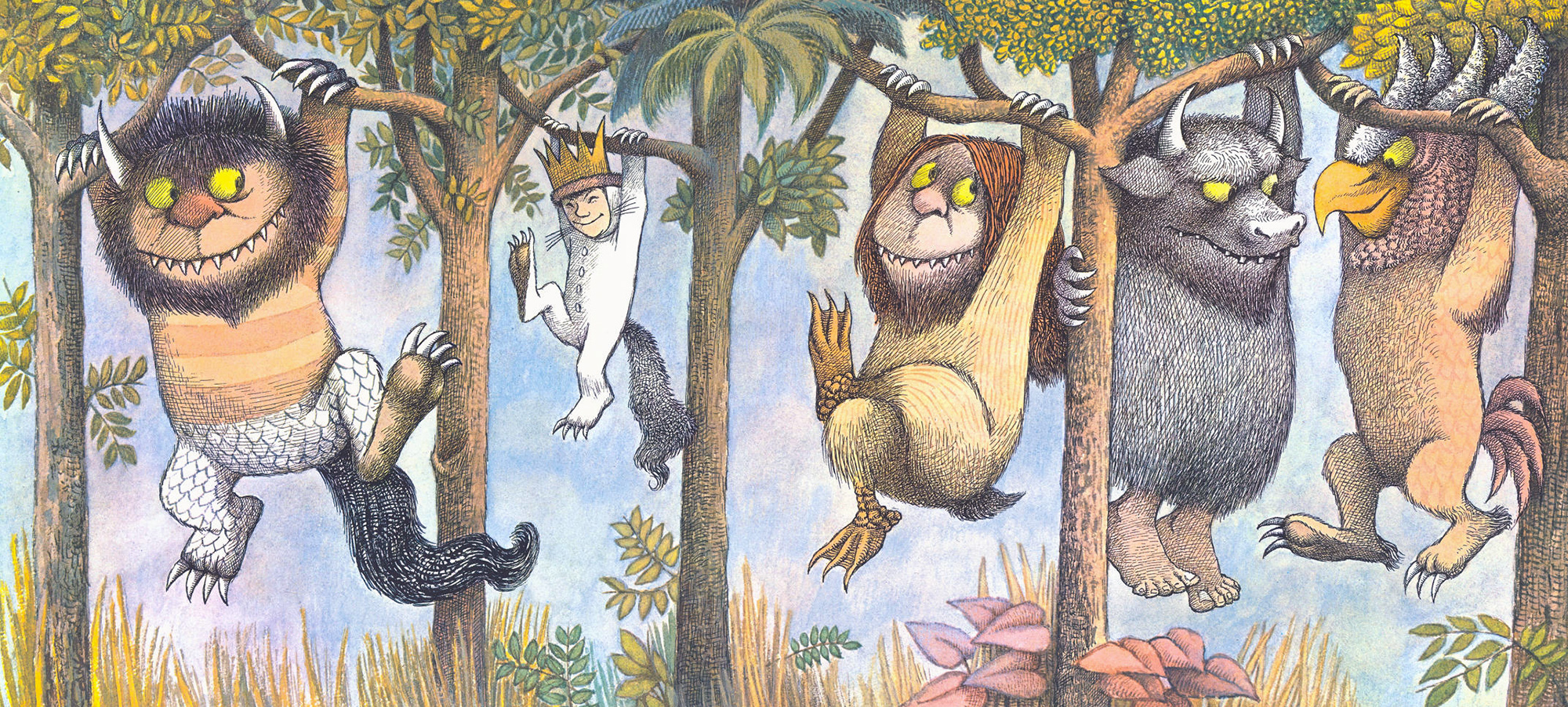

Maurice Sendak Original prints from ‘Where the Wild Things Are’

A wonderful example of the rich and playful world of childhood imagination is the beloved classic Where the Wild Things Are (1963) by illustrator and author Maurice Sendak. First conceived as a picture book, it is a story that has left an indelible mark on children’s literature over the past 60 years. A mischievous boy, Max, imagines a far-off land where he can be king. Sent to bed for misbehaving, Max’s vivid imagination transforms his bedroom into an exquisite forest, inhabited by fierce beasts promising wild adventures. Upon its release, the book caused concern among some adults, who questioned its depiction of childhood resentments and rebellion. However, the story’s focus on a child’s enchanted perspective as a means of processing tumultuous emotions has since been embraced, and Where the Wild Things Are has moved beyond the page — first to the stage then to the screen.

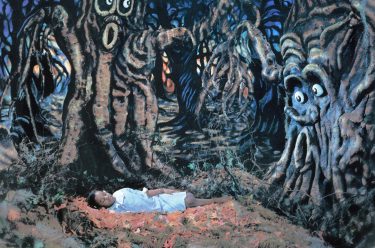

Jim Henson’s Creature Shop (designer) ‘Where the Wild Things Are’ 2009

Directed by Spike Jonze, Where the Wild Things Are (2009) develops Maurice Sendak’s original story’s themes of childhood turmoil and frustration. In Jonze’s live-action telling, Max’s anguish is grounded in the ordeal of his parents’ divorce and the prospect of a new step-parent, and his inability to articulate grief, fear and fury at the world changing around him. The film is filled with an array of endearingly fearsome creatures, with their sharp teeth and claws reflecting Max’s inner psychological experience. The film is represented in the ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition through the wolf-suit costume, with crown and sceptre, worn by the actor playing Max on screen, alongside the captivating animatronic puppet costumes of ‘Wild Things’ Carol and Douglas (illustrated), created by Jim Henson’s Creature Shop.

Brian Froud (costume designer) ‘Labyrinth’ 1986

Props from ‘Labyrinth’ 1986

The evolution of fairy tales on screen from the 1970s onwards was influenced by North American master craftsman, puppeteer and filmmaker Jim Henson. Like Maurice Sendak before him, Henson believed that darkness in childhood tales was an important part of processing troubles. Notable for his insightful characters and storytelling ability, Henson’s practice is represented here by his cult-classic coming-of-age film Labyrinth (1986). Told from the viewpoint of Sarah, a sulky teenager whose family dynamic has been splintered by divorce, remarriage and a new sibling, she envisions herself as a put-upon princess while babysitting her infant brother. Sarah wishes to be free of the crying child, and the wretched obligation to her (not so wicked) stepmother. Her wish is granted by the Goblin King, who takes the baby, thrusting Sarah into an adventure in a parallel world — filled with an ever-changing labyrinth, talking creatures, a peach of forgetting, and an otherworldly ballroom sequence — to retrieve him. The dreamlike logic of the film shifts between states of childhood and adulthood as Sarah realises she is not as ready as she thought to be grown up.

The film’s movement between worlds is represented in the ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition by props drawn from Sarah’s pre-adventurous life — selected toys, a Labyrinth book, a bookend and a music box from her bedroom, alongside a film clip that foreshadows their impending transformation into life-size characters and locations in the world of the labyrinth. The magical realm is represented by the props of a fairy-spraying gun, a 13-hour clock and crystal orbs, and a costume worn by the actor playing the Goblin King. These elements are brought to life with a clip of the film’s iconic Escherian staircase scene.

Lewis Carroll ‘Xie Kitchin, Captive Princess, 26 June 1875’ 1875

Elsie Wright & Frances Griffiths ‘Cottingley Fairies’ photographic series (1917–20)

The slippage between real life and a fairy tale realm was very tangible for Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1872). A lecturer in mathematics at Oxford University, Caroll was known as the Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. It was under the pen name of Lewis Carroll, however, that he revealed his love of writing, theatre, puppetry, photography and magic. Carroll often photographed his friends’ children enjoying the theatrics of dress-ups and play-acting, capturing these moments in a series of hand-tinted albumen photographs. The photograph Xie Kitchin, Captive Princess, 26 June 1875 shows one of Carroll’s favourite subjects, Alexandra (‘Xie’, pronounced ‘Eck-sy’) Rhoda Kitchin, who was the daughter of his colleague, Reverend George William Kitchin. In the photograph, Xie is dressed as a sullen princess awaiting her prince. This image is one of four taken on the same morning with her three younger brothers, George, Hugh and Brook, in which the family acted out a variety of stories.

The playful ‘Cottingley Fairies’ photographic series (1917–20) by cousins Frances Griffiths and Elsie Wright, captures the whimsy of their childhood imagination and their wish to bring magic into the real world. Created in the northern English village of Cottingley when they were 9 and 16 years old, respectively, the series of five photographs were reportedly taken by the girls for their parents as ‘proof’ that fairies were responsible for their dishevelled appearances after playing in the garden every day. The photographs were taken at a time when spiritualism — a religious movement that believed one remained in spirit form after death — was in fashion, and photography was widely understood to be a truthful medium. They were shown at a local meeting of the Theosophical Society in mid‑1919 by Elsie Wright’s mother, where they were met with enthusiasm. Many were convinced of the images’ authenticity over the months that followed, including Sherlock Holmes author and prominent spiritualist Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Understood as scientific evidence of a ‘faerie’ realm, the photographs reflect a moment in history when advancing technology held the possibility of connecting people with the supernatural — a poignant hope in the context of World War One, when many families sought contact with fallen loved ones. It was not until more than 60 years later that Elsie and Frances admitted their photographs were created through the artful use of paper cut-outs.

The ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition is at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), Australia from 2 December 2023 until 28 April 2024.

‘Fairy Tales Cinema: Truth, Power and Enchantment‘ presented in conjunction with GOMA’s blockbuster summer exhibition screens at the Australian Cinémathèque, GOMA from 2 December 2023 until 28 April 2024.

The major publication ‘Fairy Tales in Art and Film’ available at the QAGOMA Store and online explores how fairy tales have held our fascination for centuries through art and culture.

From gift ideas, treats just for you or the exhibition publication, visit the ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition shop at GOMA or online.

#QAGOMA